10.09.2024

1.

“The price of greatness is responsibility,” said British Prime Minister Winston Churchill during his visit to Harvard University in 1943. This phrase remains a cornerstone of global political thought, defining the boundaries of what is acceptable for public figures while simultaneously creating a collision between the desirable and the possible. It was precisely into such a collision that Yulia Navalnaya—widow of the well-known Russian opposition politician Alexei Navalny—found herself at the political forum in Slovenia.

After her husband’s murder, Yulia Navalnaya became, in the eyes of many, a symbol of resistance to Putin’s regime, transforming into one of the loudest speakers of the “Russian opposition.” It should be noted that, in our opinion, the term “Russian opposition” is not entirely accurate. In the current circumstances, it carries little meaning and is more applicable to participants in “political emigration” rather than to a real political opposition. However, it should be acknowledged that political emigration can quickly transform into a political opposition or even a real government—as history has shown with the “sealed train” [Lenin’s return to Russia]—if the right conditions arise in a given country.

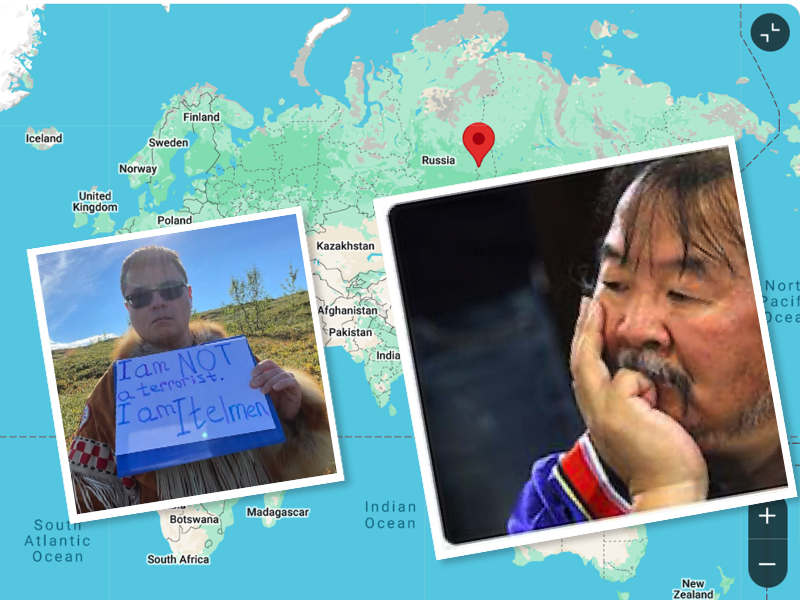

At the Strategic Forum in Bled, Yulia Navalnaya delivered a speech arguing that Europe should stop making tactical decisions regarding Russia and instead develop a long-term strategy. From the perspective of political fundraising, this was a flawless speech. However, it triggered extensive discussions within the “ethnic emigration” community. This term can be loosely used to describe political activists and human rights defenders—representatives of Indigenous peoples and ethnic minorities of Russia—who, due to circumstances, found themselves in forced exile.

With all due respect to Alexei Navalny—a courageous and consistent political opponent of Putin—it must be acknowledged that for Ukrainians, he remains infamous for his phrase: “Crimea is not a sandwich that you can just take and give back.” No subsequent actions or even his martyrdom have been able to change this perception.

Following the Slovenian forum, Yulia Navalnaya risks being remembered by Russia’s non-Russian peoples as the person who threatened (apparently, after coming to power) to “find those” who advocate for the “decolonization” of Russia.

We will return to the presentation style of Navalnaya’s speech later. But even the mere act of placing the term “decolonization” in quotation marks in a political declaration signals an intent to downplay its significance—to portray it as an artificial and insignificant phenomenon.

Meanwhile, decolonization is a far broader concept than the mere division of large countries into smaller ones, as Yulia Navalnaya suggests. Recent political history clearly demonstrates this fact. There are many interpretations of decolonization worldwide: legal decolonization, сultural decolonization, decolonization of art and cinema, decolonization of science and many more.

Furthermore, decolonization is becoming a dominant theme in contemporary politics. How else can we describe Putin’s war against Ukraine, if not as a colonial war? How else can we define Ukraine’s resistance, if not as an anti-colonial struggle? The empire seeks to reclaim what it believes is “its own.” The former colony resists.

Yet, in her speech, Yulia Navalnaya condemns decolonization, equating it to nothing more than the arbitrary dismantling of a large state into smaller, insignificant ones: “Supposedly, our country is too big, and therefore, it must be divided into a couple of dozen small and safe states.”

However, if we recall the classic definition of decolonization—as the process of gaining political independence by European colonies after World War II—we can infer that for some in the British Empire, its collapse was a tragedy that fragmented a great nation into many small ones. But for dozens of nations around the world, this process meant the attainment of independence, human dignity, and national identity. Surely, they did not care what British propaganda thought of them.

The deliberate belittling or diminishing of social phenomena and their terminology is a common tactic used by the ruling class (we hesitate to use Marxist terminology, but it is highly appropriate here) to counteract such phenomena. This approach has been used repeatedly in history—as exemplified by Lenin’s famous remark about: “The intelligentsia, those lackeys of capital, who imagine themselves to be the nation’s brain.”

A public figure employing such a strategy seeks to assert their “correct” view while simultaneously undermining or discrediting other interpretations. This is the exact rhetorical approach that Vladimir Putin employs when discussing the collapse of the USSR, calling it: “The greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century.” Yet, he fails to mention that this “catastrophe” allowed millions of people—for example, those in the Baltic states—to gain freedom and economic prosperity in democratic societies.

By making her statement about decolonization, Yulia Navalnaya unwittingly echoes Putin’s rhetoric, which claims that: “After the collapse of the USSR, our geopolitical adversaries sought to further dismantle what remained of historical Russia—its very core, the Russian Federation itself—and to subjugate whatever was left to their geopolitical interests.” – Vladimir Putin, former director of the FSB.

Thus, Yulia Navalnaya, whether intentionally or not, speaks from the standpoint of an imperial elite. She reproduces Putin’s message about “protecting the majority”, while ignoring the rights of minorities seeking freedom.

This explains the wave of outrage that Navalnaya’s speech sparked among ethnic activists and Indigenous representatives. They argue that: “Whether it’s Putin or Navalny, the Kremlin remains an empire. No matter who is in power, they will inevitably defend the interests of the empire.”

We remember the communists, who crushed the aspirations of the peoples of the USSR for self-determination with an iron fist while simultaneously supporting it worldwide, primarily in the territories of Western empires. Then came the democrats, led by Yeltsin. Those who could not be physically held back (the union republics) were let go. Where there was strength, they clung with a death grip (the two Chechen wars). Then came the Putinists, who began to speculate about the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe,” and then returned to their usual practices—military actions in Georgia, Crimea, Donbas, and a full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

And in the case of Navalnaya coming to power? How will she act? Will she do the same under a democratic guise? How will Yulia Navalnaya act if she becomes the president of the “Beautiful Russia of the Future” (BRF), for example, regarding Chechnya, where almost no Russian population remains and which, hypothetically, according to the democratic standards of the BRF, would seek independence? Will Yulia Navalnaya engage in negotiations? Will she allow a referendum to be held? Or will she argue that “our country is too big to be divided into a couple of dozen small and safe states”—and send in the troops?

And if the Kremlin, under Navalnaya’s leadership, agrees on the necessity of granting independence to Chechnya, and then Tuva, where the Russian population is around 10 percent, also requests independence? Will there be differences in approaches? If so, why? And how is Tuva different from Sakha (Yakutia)? And so on.

We don’t want to delve into lengthy arguments, but it is still worth mentioning the passage in Yulia Navalnaya’s speech about people with a “shared background and cultural context.” In our view, the residents of the USSR had no less of a common background than the residents of today’s Russia, just as the residents of Yugoslavia once did. Other examples can also be recalled. We can see right now how this “background” works in practice—just look at the reaction of Russian citizens to Ukraine’s occupation of part of the Kursk region. Did they rush to volunteer to defend the Kursk region, refusing to give up “a single inch of Russian land”? Or are they still going to theaters in Moscow and watching evening entertainment shows? That is what this common background really looks like. On the surface, it seems to exist, but in reality, it is not so common after all. The language is shared—well, New Zealand and the United Kingdom also share a common language.

The authors see no reason to engage in an extensive discussion of this passage, also because we have closely followed the debate that unfolded on the Internet following Yulia Navalnaya’s speech. It is enough to cite just a few comments that illustrate how “common” this “background” really is:

- “Yulia, the common background we, Caucasians, share with you is that you have historically been occupiers. As for a common cultural context—there is none. We have simply learned to understand you in order to defend ourselves, but you know absolutely nothing about us.”

- “Then why should people with different backgrounds and different cultural contexts have to live in the same country?! Culturally, you have more in common with Ukrainians than with Chechens, yet Ukrainians do not want to live in the same country with you, while Chechens are obligated to?”

And it would be interesting to know how many volunteers Vladimir Putin would have recruited for the war against Ukraine if he had not been paying sums that are astronomical by the standards of Russia’s hinterlands, if he had not been recruiting prisoners into his army. How many volunteers would have gone to war in the name of the “common background”? And does Yulia understand how quickly this so-called “common background” can become not so common—after yet another meeting in Belovezhskaya Pushcha?

For us, the most important aspect of such discussions is DIALOGUE—the opportunity for both the strong and the weak to speak, for both the “great” (recalling Churchill’s words) and the poor and wretched.

But dialogue cannot be a monologue. And Yulia Navalnaya’s statement at the forum in Slovenia can only be described as a monologue of a representative of the white dominant majority. We would like to make a clarification: in the Russian context, this wording may seem tactless, but in international practice and, even more so, in the decolonization discourse, such definitions are not unusual.

It is precisely this circumstance that, in our view, is the key reason for the outrage among representatives of ethnic minorities and Indigenous peoples (decolonial activists, if you will) when the future is discussed by representatives of the current political emigration—the adherents of the “Beautiful Russia of the Future.”

Their future—the future of decolonial activists, their relatives, loved ones, and their peoples—is being discussed without them, and they are being told how they are supposed to live—is this not an imperial approach? In exactly the same way, Vladimir Putin speculates about how Ukraine is supposed to live as part of the “Beautiful Russia of the Present”—but for some reason, Ukraine does not want this.

For the Indigenous small-numbered peoples of the North, Siberia, and the Far East (and we have written about this more than once), who live a traditional way of life, what matters most is not the size of the country, not the system of governance, not the person in power, but the fundamental principle of the state’s commitment to democracy, human rights, and the right of peoples to self-determination. And this principle can be successfully implemented both within a common state in the form of the Beautiful Russia of the Future and within separate national state entities.

For us, democracy, freedoms, and rights come first—not the form of government or the surname of a particular person in power. And in this, we hope, we have no contradictions either with the representatives of the “Beautiful Russia of the Future” or with the representatives of the “League of Free Nations,” who propose the dismantling of the Russian Federation and the creation of independent national states in its place.

Continuing the discussion of Yulia Navalnaya’s thesis on decolonization, we recall an interview with the well-known representative of Russian “political emigration,” Gennady Gudkov, in which he also criticizes this term, arguing that its inclusion in the PACE Resolution plays into the hands of Putin’s propaganda. In this regard, we believe:

- Putin’s propaganda does not care what Gennady Gudkov or ethnic activists say. Propaganda can turn shit into candy and vice versa. It does not matter what kind of material is thrown into the furnace as fuel.

- The influence of Gennady Gudkov himself, as well as that of Yulia Navalnaya and the “Russian opposition” as a whole, on the situation inside Russia today is so minimal (which, unfortunately, must be acknowledged) that it is essentially indistinguishable from the level of influence of ethnic activists demanding self-determination for their peoples (which also, regrettably, must be acknowledged). These messages, at this moment, have almost no effect on the internal situation in Russia, while at the same time being successfully used by Russian propaganda in its “holy war” against the West.

Therefore, in our view, this discussion is, in its purest form, a competition of ideas—on one side, Gennady Gudkov and Yulia Navalnaya advocating for the “Beautiful Russia of the Future,” and on the other, ethnic activists arguing for the “dismantling of the empire.” And the dominance of Gudkov and Navalnaya’s position in the West is merely evidence that there are more Russians than non-Russians. That Russian intellectual, financial, and administrative potential surpasses the “ethnic” potential. This is the reality both within Russia itself and in emigration.

That is, this discussion as a whole is a replica of the decolonization discourse. If we draw a historical parallel, we could say that the Siberian peoples in the 16th–18th centuries, being conquered by the Cossacks, also had their own perspective on the events taking place. However, their perspective was crushed by the viewpoint of the Cossacks, who represented the empire. And primarily because there were more Cossacks (literalists will immediately rush to refute this thesis, but what we mean is that the empire could send endless waves of conquerors, whereas the peoples being subjugated—quickly exterminated by firearms and diseases—were a finite category), the Cossacks were better educated, and their weapons surpassed those of the natives. So, in Navalnaya’s case, with her speech in Slovenia, we see nothing but history repeating itself.

2.

In this article, we would also like to address the form in which Yulia Navalnaya’s speech was presented, as prepared by her team. We see that the main discussion following her speech has revolved around the fundamental issue—whether Russia is an empire and how it should be decolonized. However, few have paid attention to the way the material was presented, which we consider no less important.

It should be noted that Navalnaya’s key thesis on decolonization, which provoked a fierce response from decolonial activists, was presented in slide №7 of the Russian-language version of her Instagram post. The passage on decolonization was visualized using a technique that, in the Russian context (if the broader context is absent), can be perceived as threatening: “Finally, we will also find those who talk about the urgent need to ‘decolonize’ Russia. Supposedly, our country is too big and must be divided into a couple of dozen small and safe states. However, these ‘decolonizers’ cannot explain why people with a common background and cultural context should be artificially divided. Nor do they say how this should even happen.”

Is it possible that such a slide with a “threat” was created by accident? Possibly. Or maybe it was made out of stupidity? Also possible. The subsequent explanations that this slide was taken out of context do not seem reasonable to us. Such a reaction could have been anticipated in advance—it was obvious. Especially when dealing with such a sensitive matter as national identity.

Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that such a visualization of the thesis about decolonizers was intentional. But why?

The use of such a visualization of negativity seemed strangely familiar to us, evoking a sense of “Déjà vu.” It reminded us of another work by the “Navalny Team”—the famous film “Traitors” about the 1990s. A film about the rise of democracy in Russia and the coming to power of the dictator Putin.

Following the release of this film, a major discussion began in the Russian-speaking internet. Many felt (and, apparently, justifiably so) that the film’s creator, Maria Pevchikh—one of the ideologists of the modern “For Navalny” movement—not only recounted the events of the 1990s but also personally attacked Mikhail Khodorkovsky.

Many asked the question: “Why start a war against Khodorkovsky now, when it is more important to unite around the idea of opposing Putin?” From the perspective of a politician—especially a politician who is thinking about power in a future Russia—this action, an attempt to “eliminate” Khodorkovsky, who could have been a potential ally, seems irrational (at least at this stage).

The authors of this article rewatched all three episodes of the film. More than once or twice, Maria Pevchikh in her film shows photographs of Khodorkovsky at moments when she talks about “traitors,” about “oligarchs who sold out democracy,” and so on. Whereas, for the sake of historical fairness, it would have been enough to include a single episode featuring Khodorkovsky in the context of “loans-for-shares auctions” (considering the pragmatism of alliances necessary to oppose Putin). But Maria Pevchikh, time and again, nails Mikhail Khodorkovsky to the pillory of oligarchy.

From a strategic standpoint, the film “Traitors” is a mistake. It turns potential allies into enemies and weakens the ability to resist Putin’s regime. It does not unite but divides. And numerous commentators on the film rightly criticized Pevchikh, saying that she did not delve into the topic, did not examine the facts, and presented only one side, effectively turning the film into a propaganda product.

The critics’ main complaint was as follows—while the film is valuable in that it sparked a discussion about the 1990s, a period that has not yet been fully reflected upon in the Russian consciousness, its release was extremely untimely, sowing discord among potential allies. This is not how sensible politicians act (how can we not recall the aforementioned Churchill, who struck a “deal with the devil” to achieve victory?).

However, we believe that the film “Traitors” should not be assessed from the perspective of political strategy at all. In our view, the film does not carry a political agenda. If we look at Pevchikh’s team’s actions from a different angle—through the lens of political fundraising and the opportunity to eliminate a competitor—then her film becomes a deliberate and rational move. Maria Pevchikh’s team strategically targets several objectives: creating a watchable product, presenting the younger generation with their own version of the 1990s and Vladimir Putin’s rise to power, thereby “fighting the regime” while simultaneously discrediting a competitor.

Some may wonder—what does fundraising have to do with this, and what does Khodorkovsky have to do with it, given that he is already a wealthy man? However, political fundraising is not just about money. It is also about the ability to establish contact with decision-makers, the opportunity to sell one’s ideas to politicians—in this case, Western politicians.

Furthermore, thanks to a tip from our colleague Anna Gomboeva, we noticed a difference between the Russian-language and English-language versions of Yulia Navalnaya’s Instagram post. In the English-language version of Instagram, the passage about decolonization is absent. Anna suggested that Navalnaya’s team, taking into account the West’s stance on decolonization issues, Black Lives Matter, and similar topics, removed this paragraph from the English version to avoid drawing the ire of Western human rights activists.

In the speech itself, which was delivered in English, there is no mention of Navalnaya’s team planning to seek out decolonizers (after coming to power): “Finally, there are those who advocate for the urgent ‘decolonization’ of Russia, arguing to split our vast country into several smaller, safer states. However, these ‘decolonizers’ can’t explain why people with shared backgrounds and culture should be artificially divided. Nor do they say how this process should even take place.”

In the speech itself, which was delivered in English, there is no mention of Navalnaya’s team planning to seek out decolonizers (after coming to power): “Finally, there are those who advocate for the urgent ‘decolonization’ of Russia, arguing to split our vast country into several smaller, safer states. However, these ‘decolonizers’ can’t explain why people with shared backgrounds and culture should be artificially divided. Nor do they say how this process should even take place.”

This approach and method of presentation raise many questions for us and create a sense of ambiguity and double standards. It turns out that one message (a confrontational one) is sent to the Russian-speaking audience, while a different one is directed at Western partners.

It can be assumed that slide №7 in the Russian-language Instagram was deliberately created precisely to provoke a storm of angry reactions. In our view, to put it plainly, this was a deliberate provocation.

We are already seeing emotional statements from some ethnic activists online, comparing the Russian people to fascists, calling to “stop kissing Russians in …,” or even urging to wipe “Moscovia” off the face of the earth.

And these emotions can easily be used in new rounds of the infamous political fundraising, presenting them to Western politicians as follows: “Look at these decolonizers—this is a horde of militant chauvinists. Right now, they are simply raging, but give them power, and they will drive all Russians out of their republics (or slaughter them).”

From the perspective of a politician who is building a strategy for a real rise to power in a multinational country, the publication of slide №7 is short-sighted and mistaken. From the perspective of political fundraising, it is ideal. Another round of smearing competitors in the struggle for Western attention, while at the same time remaining unclear to the Western reader, who will see only the English text and will not delve into the details of the Russian-language version.

3.

However, it must be acknowledged—Yulia Navalnaya, in her speech, posed a key question (a “research question,” so to speak): How is this decolonization supposed to happen at all?

It is worth noting that the term itself has recently been worn out from various sides, and some have begun to shy away from it. This has been influenced both by Yulia Navalnaya’s speech in Slovenia and other similar statements by political émigrés, as well as, unfortunately, by the speeches of some decolonial activists. Both sides often reduce the understanding of decolonization to the simple idea of “dividing the big into the small.”

Meanwhile, decolonization, as we have mentioned before, is a broad concept. For example, for the Indigenous small-numbered peoples of Russian Siberia and the Arctic, the primary concern is the ability to maintain their traditional way of life—to hunt, fish, and herd reindeer freely on their ancestral lands, as well as the ability to preserve their customs, culture, languages, and the traditions of their ancestors.

For us, the concept of decolonization, the mirror image of which is the concept of peoples’ self-determination, means the ability of Indigenous communities to make decisions on seemingly simple but vital issues—where to fish, when to gather, and how to hunt. And if not by themselves (we are not reactionaries and understand that Indigenous peoples do not live in this world alone), then at least we would like decisions to be made with consideration for these communities’ opinions. So that a virgin forest does not suddenly turn into a coal mine where unscrupulous profiteers extract yet another billion for themselves.

In international law (which, in reality, is the only framework that protects the rights of Indigenous and small-numbered peoples), the necessary mechanisms have long been developed—co-governance mechanisms, the framework for ensuring Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC), and others. It seems that to explain our position on this issue in detail, another article would be needed (perhaps more than one).

However, we understand that other members of the public may interpret the concepts of decolonization and self-determination differently, including as the creation of separate ethnic states. And that is normal. It is a natural aspiration to gain independence in determining one’s own destiny. For the Indigenous small-numbered peoples of Russian Siberia and the Arctic, such a solution is most likely impossible due to their small population. But for other, more numerous peoples, the desire for such a solution does not seem unnatural to us.

Another matter is that, in our view, some representatives of the ethnic diaspora are being disingenuous when they claim not to understand why many in the West are so afraid of the creation of independent and democratic national states on the current map of Russia. It seems unlikely that any Western politician fears the emergence of three dozen independent, prosperous, and democratic Estonias on the territory of present-day Russia— even if it were to happen tomorrow.

It is not this that they fear. They fear violence, having learned from the bitter experiences of Yugoslavia, the Middle East, and other regions. They fear even greater bloodshed (especially considering the presence of nuclear weapons) than what is already happening today.

In our view, this concern cannot be dismissed as entirely unreasonable, which is precisely what some representatives of the Russian political emigration exploit for political fundraising purposes.

Nevertheless, we (paradoxical as it may seem) believe that the mere fact that decolonization was mentioned in the speech of such a well-known public figure as Yulia Navalnaya can already be considered a positive sign. For us, this means that the community of those who see their homeland and national interests within the territory of present-day Russia is beginning to ask the right questions.

The authors of this article do not have a ready answer to these questions. In our view, decolonization and self-determination are not an endpoint; they are a process.

However, we will still have to seek an answer to this question together, regardless of whether you envision the Beautiful Russia of the Future or seek to bring freedom to your own peoples.

But we can say with certainty that the first step in this direction must be dialogue and a mutual rejection of violence and insults. Dialogue, so that we can hear each other. As one literary character once said: “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view… until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.”

And in conclusion, the authors are certain that only the victory of the Ukrainian people in this anti-colonial war can help the peoples of Russia gain freedom; otherwise, it will mean the continuation of the empire.

Pavel Sulyandziga, Dmitry Berezhkov